PICO WINE: ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST UNIQUE WINE REGIONS (GENESIS – PART I)

The first time I stepped on Pico island, one of the nine islands in the Azores archipelago, I had no idea of what I was about to discover.

Contrary to what is common, I didn’t plan this trip myself. I was invited by some dear friends to join them on a 10-day trip to the Atlantic Islands of the Azores, specifically to the central group – Pico, Faial, and São Jorge.

Of course, I had read something about the Azores, particularly about the islands we were supposed to visit. I even emailed the Azores Tourism asking for their brochures, books, and maps – I can’t help myself!

So, when we took the plane I carried with me a few jottings, with a selection of some treks and sightseeing but… as a foodie and as an anthropologist passionate about people, I couldn’t imagine what I was about to discover!

Lots have changed since then, for me.

And during these last decades, as we’re about to find out, also for Pico Island!

Pico Wine, a hidden treasure

One of the most unique wines in the world, it’s a hidden treasure!

Although people are becoming increasingly familiar with Portugal’s wine regions, very few know about Pico wines. And even fewer have had the opportunity to taste it!

Unesco Landscape (August, 2021)

The “cursed” island as many called it, the “monstrous, hideous and uncultivated” island (Chagas, 1717) with such dark stone that “seems to have been devoured by all the fire from hell” (Brandão, 2011) is presently a fantastic and enchanting territory, absolutely fascinating, with unique characteristics, in what concerns the wine, but also the culture, the nature, and their inhabitants.

Pico wines come from vines that grow from lava soil and flourish on the rock. All the work is done manually and none of this has changed in 500 years, when the first settlers introduced grape growing in Pico.

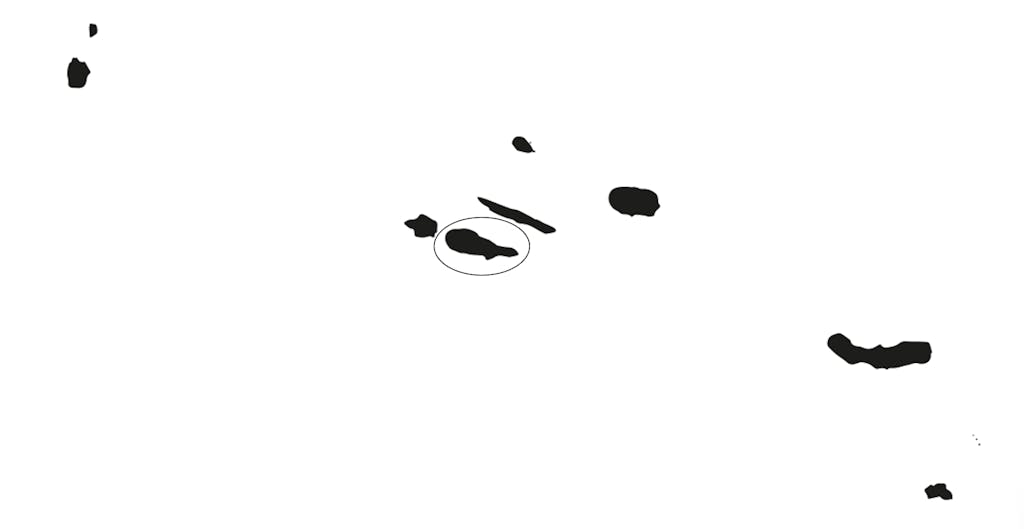

This unique ecosystem, where the black volcanic rock dominates the island, associated with the locals’ tenacity, produced, against all expectations, a volcanic, mineral and salty wine which is unique in the world, and a singular landscape – exceptionally well-preserved and fully authentic in its setting, materials, continued use, function, traditions, techniques – which is considered a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2004.

From an aerial perspective – apart from the imponent Pico volcano mountain – what struck me was the strangeness of the intriguing labyrinthic forms of the wine landscape. Full of details, these black rocky lines guide our eyes endlessly, as if we were supposed to decipher a hidden message, a story that is waiting to be unveiled and that is constantly being written in daily life.

As we will discover, Pico island is a place of strength, obstinacy and resistance. It’s also a magnificent example of how farming techniques and practices can be adapted to a secluded and challenging environment.

Situated at the periphery of the world wine markets but considered a product of excellence, Pico wine represents, in our perspective, the subversive and heroic position of a community, materialized in these exclusive, distinct, and limited editions bottles of wine!

The early steps of Pico Wine

The so-called cursed island

Pico island is geologically the youngest island of the volcanic Azores archipelago.

Characterized by the highest mountain in Portugal, an extinct volcano named Pico, which is 2351 meters high, this island is located in the middle of the Atlantic ocean, about two and a half hours flight from Lisbon.

Together with Faial and São Jorge (reachable by boat), these are called the “triangle islands”.

Pico is the second largest island of the Azores, with only 14 000 inhabitants (which represents less than 6% of the population of the Azores) – contrasting with the second half of the 16th century when Pico represented the third largest human agglomeration of the Azores.

This young geological age combined with recent eruptions and lava flows (in 1572, 1718, and 1720), have shaped the island with volcanic stone. Compared with São Miguel island, which is more than 5 million years old, Pico’s basaltic rock has not had the time to degenerate and produce soil.

As Manuel Costa, the director of Pico Wine Museum, states: “Pico was named a hideous, haunted island, a lava field, re-scorched and smoldering, full of stone that generated nothing!”

These geological characteristics challenge any agricultural attempt which, contrasting with the other fertile islands, made Pico the last island of the central group to be populated.

Discovered in 1432 (by Gonçalo o Velho Cabral), only from the 1480s onwards was Pico island significantly populated by Portuguese, French and Flemish settlers (in part, due to an agreement between Isabella de Portugal and Duchess of Burgundy, to create a safe and neutral exile-like region for nobles from Flandres when the Duke of Burgundy was invading this territory).

Unlike the other islands in the Azores (São Miguel, Terceira) which stand out because of their diversity and abundance in agriculture, the geological particularities of Pico – and also São Jorge island – made them less favorable for cereal culture and therefore, the need for locally adapted projects emerged.

In São Jorge the extension and quality of the pastures is ideal to raise cattle for meat and for the famous DOP São Jorge cheese, among others!

But the most incredible achievement takes place in Pico, where vines flourish from the rock, “as a miracle”, as a subsistence strategy (just like whale haunting in the 19th and 20th centuries), first for local consumption and later, for exportation (Meneses, 2011).

As Manuel Costa shares, with visible emotion, “The engineering and inventiveness of creativity arises here with the construction of Pico’s vineyards. And, to me, that is a miracle. How was it possible to do this all those centuries ago?”

São Jorge green and luxurious ‘fajãs’ (July, 2021)

The blessed vineyards

The first vineyards were introduced to Pico back in 1450, by Frei Gigante, a Franciscan friar who brought the first rootstocks of Verdelho, a white grape imported either from Cyprus or Madeira (there is no consensus about its origins).

Even though the biggest wine area we can nowadays find in Pico is on the west side of the island, near Madalena village, Frei Gigante first planted vineyards in the south, around his home, in a region now known as Silveiras (the name derives from the fact that Frei Gigante protected the vines with brambles – silvas in Portuguese). According to Frutuoso (1981) vines then extended to Lages (also in the south) and São Roque (north).

José Costa (August, 2021)

For José Costa, a native of Pico island and a history lover, there is no other reason for these first wine plantations than the intention to use the wine for mass – even if Verdelho grapes are white, challenging what is normally the assumption that during religious celebrations red wine is the standard. Interestingly, there is no record that points towards the fact that wine ought to be red to represent the blood of Christ.

The fact that, in his article, Frutuoso does not make any reference to the western side of the island, now considered Unesco Heritage, makes us think that only after the 16th century did vines start to be planted in this area. It seems, in fact, that until then, Madalena’s surroundings remained unpopulated and uncultivated, certainly because of the harsh lava stone soil.

Ironically, this inhospitable soil would eventually be the cradle of a wine revolution that projected the Azores into the world during the 18th and 19th centuries.

A subsistence strategy

In the 16th century, Pico island was already considered the best for wine production (when compared with São Jorge, Terceira and São Miguel), both regarding quantity and quality (Medeiros, 1994).

Motivated by the geographical proximity and attracted by Pico’s wine potential, many wealthy families from Faial gradually bought lands around Madalena, with the intention to plant vines.

Generally speaking, taking into consideration the island’s conditions and history, picarotos (natives from Pico) certainly did not have the same economic power.

We can also understand the effort invested in what would later be considered legendary work as an act of necessity, in an attempt to explore and transform the intrinsically limited area of an island looking for alternative ways to subsist.

The transformation of Pico’s landscape

The inventiveness of Picarotos

Pico Wine Museum housed in building that once belonged to the Convento do Carmo (March, 2022)

A process of reorganization of the territory began, specifically around Madalena village. With it came a gradual emergence of manor houses along the coastline, owned by wealthy families that lived most of the time in Faial, but also the religious order of Franciscans, Carmelites and Jesuíts.

The owners of the lands only casually visited Pico and they were not significantly involved in all the epic work that needed to be done in order to extract wine from this area.

This inventive work which became the norm from this moment onwards, that would dramatically transform Pico’s physiognomy and that was much later classified as Unesco Heritage (2004), was done by subcontracted locals from Pico, picarotos, who couldn’t economically afford to buy the lands and invest in them.

Knowing the island like nobody else and having to provide for their families, they were responsible for this dramatic landscape transformation.

But how did the heroic picarotos achieve this laborious task of planting vines in rock?

From lava rock only vines can flourish

The soil, brough from Faial in small sailboats, was poured into each opening and a vine cutting was planted inside at an angle so it would grow along the ground instead of upright.

At this time, the soil was purchased at fifty ‘reis’ for every forty liters. But this soil was in fact being extracted from the lands in Faial that belonged to the same wealthy families who bought lands in Pico. Clearly, another disadvantage for any ‘picoroto’ who tried to own its own vineyards.

But deciding to plant vines in the hardest soil on the island was not the only challenge.

António Maçanita, one of the founding members of Azores Wine Company, mentiones that the combination of a cool climate, due to the latitude and the Atlantic influence, with the foehn wind effect, forced Pico inhabitants to plant their vineyards right by the sea, to guarantee a greater amount of sunshine and maturation.

In Pico, vineyards should always be planted “where you can hear the singing of the crab”, a sentence recently coined by this enologist, underlying the strong relation between the sea, the salt and Pico wine.

Pico Unesco Heritage landscape (March, 2022)

Landscape physiognomy

In order to protect the vineyards from the sea and the wind, and to make the most of the climatic and geological conditions of the stony land, It was therefore necessary to sort out the stone and use it for protection.

The inhabitants of Pico structured the land in an impressive mosaic of local, irregular, weatherworn, black basalt stone walls, called “currais”. Larger stone walls, “jeiros”, separate the land from one farm to the next.

These man-made rock labyrinths and walls raised to protect the vineyards in this harsh environment are so massive, that if they were to be put in a straight line they could go around the Equator line not once… but twice!

This grid of square plots outlined by black basalt walls where the vines are planted, extends towards the horizon, but there’s one or two vineyards per plot! Vines are pruned in order to keep the plants close to the ground, while being protected by these walls.

The “currais” create a microclimate, where the small plots absorb the rain (in a rocky land that, otherwise, does not retain any water) and condition the wind during the several states of growing and maturation. Particularly the wind that comes in from the ocean, carrying salt with it.

Example of lava rocks supporting the vineyards (March, 2022)

Besides, these black lava rocks capture the rays of sun and create a warm and dry microclimate. During the day, the vineyards mature under the sun, while during the night they receive the heat transferred by the rocks.

Some stones are placed under the long and close to the ground branches in order to provide support, but also to stay warm during the night, which helps the grapes that sit on top of them to ripen.

The minerals from the lava rock (potash, magnesium, silica, iron) with all these elements (water, sun, erosion) tend to be some of the components present in the grapes producin what we define as a volcanic mineral wine.

Finally, the holes in between the millions of small stones allow the walls to be stable yet not offering way too much resistance to the wind, allowing part of the breeze and water to come through, as well as some salt which also contributes to the identity and excellence of Pico wine.

Protecting without suffocating

These rocks or “biscuits” (biscoitos, in Portuguese), the result of popular wisdom, necessity, and inventiveness are there to protect, yet without suffocating.

In fact, the salty Atlantic winds still damage a percentage of the vines, reducing their yield but leaving the ‘best’ grapes to be used for wine production. It’s in this balance, between a completely hermetic wall and an almost impenetrable basaltic lava rock, that lives what makes this stubborn, resistant, heroic wine so special, so unique, so delicious and rare!

We see it as an universal law, here metaphorically represented by this heroic work conducted in a tiny island, in the middle of the Atlantic, respecting the environment and the local specificities.

We should protect but, within the ‘right measure’. Leaving space for the others’ identity to express, allowing for error to happen, accepting the context that shapes the final product (in the case of the environment and the wine).

It seems an irony to state this, after describing this monumental work and landscape transformation. But the truth is that, along this long and hard process, the men and women who originally created this unique system, were never ‘distracted’ from the essence of their work, even if in an unconscious way: to respect and to resist the recurrent human temptation of controlling too much (at least among the western cultures).

Pico vineyards and Pico mountain hidden by the clowds (August, 2019)

Pico’s vineyard Culture: Unesco World Heritage 2004

Due to its uniqueness, the wine landscape on Pico Island which we have just described, was classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2004, constituting today the Landscape of the Pico Island Vineyard Culture, an protected area.

Lajido de Santa Luzia and Lajido da Criação Velha appear as prime examples of this art of parceling out the land, which corresponds to hundreds of kilometers of arduously erected stone walls.

Cátia Laranjo, one of our dearest Pico wine producers (August, 2021)

This spectacular coastal setting of the viniculture landscape sits at the foothills of Pico Mountain, a volcano that dominates the topography of the island.

Today, most of the “currais” in these areas are used in a way that is consistent with 19th-century techniques and traditions, thus remaining fully authentic. Viticulture practices are presently carried out by individual owner-farmers, many of them from Pico, without the use of mechanical vine-growing methods.

We have assisted to an expansion of the local wine-based industry that respects authenticity – by using currais in a way that is consistent with the techniques and traditions of the 19th century – but also rediscovering a tradition that is not a repetition of the same, but a reinvention.

Along our several trips to the Azores we have met independent wine producers, picarotos that are re-writing Pico’s history, in a more subversive position.

But how did the history of Pico’s wine evolve from the moment that unique rocky landscape was created, and was finally ready to produce wine, until nowadays?

If now the main wine producers are ‘picarotos’, how did the lands return to their families?

Pico wine was defined by moments of great success in the 18th and 19th centuries, when it even became popular among the Russian Czars, but also by a great decline in the production and by consequent land abandonment.

This is what we cover in our next Pico Wine article.

Article by :

Sílvia Olivença (anthropologist and food guide/CEO at Oh! My Cod Ethnographic Food Tours & Trips)

Photos by:

Sílvia Olivença (anthropologist and food guide/CEO at Oh! My Cod Ethnographic Food Tours & Trips)

Zara Quiroga (food writer freelancer and food & cultural leader at Oh! My Cod Pico Trips)

Want to more about the Azores islands?

Portuguese Easter sweet bread and Holy Spirit soups

Pico Wine: the history of a heroic and subversive wine (Tradition & Innovation – Part II)

Want to spend some time in the Azores, with us?

Check our culinary wine trip presentation below!