REGIONAL PORTUGUESE CUISINE: FOOD WITH A SENSE OF PLACE

“Food is everything we are.

It’s an extension of nationalist feeling, ethnic feeling, your personal history,

your province, your region, your tribe, your grandma.

It’s inseparable from those from the get-go.”

-Anthony Bourdain

Arminda and her husband take their flock of sheep to graze, in Alentejo, almost every day. From the milk, they produce local cheeses.

The famous celebrity chef, TV presenter and travel writer Bourdain always made it a point to link food traditions to their country of origin. But we could even go further and say that cuisine is a regional phenomena. Because ingredients, eating habits and typical dishes were already being crafted in certain areas before we even knew countries and nations as we do today.

Officially dating back to 1143, Portugal is one of the oldest and still existing countries in the world. But even before it was officially proclaimed a nation, what is now the defined area that forms our country was already an inhabited territory. Historians believe that people have established themselves in Portugal as far back as the 6th century B.C. and, over the centuries, we kept receiving different peoples and civilizations that passed by or even settled in the Iberian Peninsula, thus shaping our culture and, of course, food habits, until today.

Portugal: small in size, big in diversity

Just like everywhere else in the world, the availability of ingredients that shape Portuguese eating habits is also a product of our topography and geographical location. Even though Portugal is a small country, with an area of a little over 90,000 km², it is fairly diverse in terms of terrain and climate.

The north interior of Portugal is dominated by mountains, and so is the central interior part of the country. Meanwhile the Atlantic coastline extends from the north to the south, which is also known for its immense plains, particularly in the vast region of Alentejo. With these varied terrains comes a heterogeneity of climates which are also responsible for the prevalence of certain foods in some regions, while other ingredients tend to grow better in other parts of the map. The lush green landscapes of the north, particularly to the west, are indicators of frequent rains, while the landscapes of the center and south with a yellowish hue clearly show us that the weather tends to be drier around there. As such, agricultural practices in the different regions of Portugal are rather diverse. While the north is favorable to grow a larger array of crops, the harsher weather of the south is conducive towards monocultures, which is a type of agriculture that, weather and topography aside, has been pushed by the political system, particularly during our dictatorship lead by Salazar, which ended in 1974, but that prior to that had a very strong emphasis in economic growth.

Continental Portugal and Islands (Design © Silvia Olivença)

The Portuguese diet is a mix between the Atlantic diet and the Mediterranean diet (usually associated with the south of Europe), and we’re about to see how, region by region, we lean more towards one or the other. Overall, Portuguese cuisine has a tremendous sense of place, with its main ingredients being connected not only to our history and the traditions of the peoples who have settled in the Iberian Peninsula over the centuries, but to our geography too. There are various historical, cultural, social and topographical reasons why the Portuguese eat the way they do. But, no matter how you look at it, we guarantee that the array of flavors you are bound to experience when you travel around Portugal will be a delight!

Cultural influence on Portugal and Portuguese food over the centuries

The different cultures that called “Portugal” home across the ages were responsible for how we live and eat up to these days.

Wine and olive oil: a Roman legacy

The Lusitanians, an ethnic group that is today accepted as being Portugal’s indigenous people, derived from different tribes such as the Germanic Celts. The staple food of the Lusitanos, who used to eat one main meal a day, was acorn bread. During those times, wine was already being produced (in fact, the production of wine in Portuguese territory goes as far back as 2000 BC, influenced by the Phoenicians from modern day Lebanon), but it was reserved for special occasions. The daily drink of choice would be beer prepared with barley, as well as goat milk. Meat was consumed amongst the elites, which were well defined in this hierarchical militarily society. Before the domestication of the wild boar which came later on with the Roman influence, most animal protein derived from cows, horses and bovines, as well as from fishing, which was usually done aboard small leather and wood boats in the rivers.

New research shows that in some cases, we are drinking almost the exact same wine that Roman emperors did. Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images

We can trace the biggest ancient influences on Portuguese culture and food habits back to a little over 2000 years ago, when Portugal became a part of the Roman Empire which spread across many parts of what we now know as Europe. The Romans occupied Portugal from the 3rd century BC to the 4th century AD, and had half a millennium to impact the local eating habits like it hadn’t been done before. This is when products such as olive oil and wine became an everyday staple, a phenomena which carries on until today.

The Roman presence meant a productive society, with infrastructure and health conditions that made populations grow. With this growth came the need to feed more people and, with it, agricultural methods became more organized. This is when the culture of wheat seriously started, concentrating in the fertile soils of the region now known as Alentejo, which eventually helped replace the previous staple of acorn bread with softer and more nutritious wheat loaves. The Romans were also behind a lot of the food preservation methods which are linked to Portuguese cuisine even today, such as fish salting and drying, which is in the origins of one of Portugal’s most celebrated ingredients, bacalhau, aka salt cured cod. The Romans also set up several manufacturing units around Lisbon and on the south bank of the Tagus river, entirely dedicated to the production of garum. Garum is a fermented fish paste, which was used not only to pack dishes with umami flavor, but also as a source of vitamins, minerals and even protein. Made with small fish, scraps and salt, which was always abundant across Portugal and became an organized industry during these times, it was a way of making good use of pieces of fish which were not big or interesting enough to salt or cook right away. Pork, another given of the Portuguese kitchen today, became a meat of choice during the Roman times. Even though the domestication of pigs was attempted before, it was the Romans and their love for food (and orgies involving lots of eating and drinking!) who developed better techniques for animal farming, which resulted in greater abundance of meat, which was eaten fresh but also as cured charcuterie.

The fall of the Roman Empire took place with the Germanic invasions at around 400 BC. The Barbarians ended up sponsoring the so-called Dark Ages, a time of scarcity which wasn’t particularly conducive to new developments in the realms of food culture.

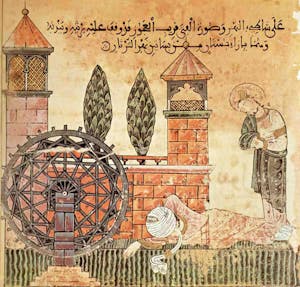

Picture of a water mill in Hadith Bayadh wa Riyadh (The Story of Bayad and Riyad).

The inventiveness of the Moors

The next civilization to leave a big mark on Portuguese society and lifestyle were the Moors from Northern Africa (more specifically from the Maghreb region), who ruled much of Portugal for around 400 years, starting from the 7th century onwards. The Islamic Moorish legacy in Portugal is palpable until today, predominantly in the regions from Lisbon southwards, such as the Algarve. Whenever you come across a Portuguese name starting with al (which means “the” in Arabic), remember that Arabic influence is behind it. This applies to places such as Almada, Alcácer do Sal, Alenquer or Algarve, just to name a few, but also to dishes like açorda (originally al thurda) and even ingredients such as alfarroba (carob, which is very prevalent in the south of the country). These muslims also brought with them many ingredients which we now take for granted, such as rice, lemons, coriander, raisins and almonds, which the cuisines of the Alentejo and the Algarve would be totally different without. Besides stand alone ingredients, the Moors also introduced the cataplana to Portugal, a pot in which we steam fish, or a mix of seafood and meat, which results in a dish of the same name as the cooking vessel itself.

The abundance of new old and new ingredients in the Portuguese territory during Moorish rule was boosted by agricultural methods, some of which were previously introduced by the Romans, but which the Moors, who brought with them Middle Eastern technology and know-how, significantly improved upon. Among other techniques, new irrigation methods were vital to increase yield from the land. Just like with the places and foods we mention above, the Moors left their mark on the Portuguese language with several words related with irrigation techniques, such as nora (waterwheel), acéquia (irrigation channel), azenha (water mill), açogue (azud, irrigation dam), albufeira (lagoon) or alcantarilha (culvert, drain).

The islamic way of life of the new rulers of much of Portugal’s territory directly clashed with the Roman influenced and thus Catholic population which was pushed to the north of the country, in an area which was named Condado Portucalense. It was from right here that the fight-back started, fronted by D. Afonso Henriques, later proclaimed Afonso Henriques I, the first king of Portugal, who eventually took Lisbon back from the Moors in 1147.

Jewish contributions to Portuguese food

After the Moors were relegated to certain areas of Lisbon (like Mouraria, one of the most eclectic neighborhoods of Lisbon in the present day, and which we explore during our Original Lisbon Food & Wine Tour) and eventually pushed towards the south of the country until they were expelled from the national territory, a new area of strong Catholic affirmation started. It was this need to impose the christian faith that in due course led to the Inquisition, which started in the 12th century in the Iberian Peninsula and lasted for hundreds of years. In spite of the catholic majority, the Portuguese social fabric at the time was still also made up with muslim Moors, as well as Jewish, which were now started to be persecuted and forced to convert to catholicism. This new imposed faith translated into different worship habits but also daily customs such as the food which families would consume.

As the Inquisition first began in Spain, a lot of Sephardic Jews found asylum in Portugal, which would anyway later on rebel against them and their particular traditions. In the 1500s, Portugal also started persecuting Jews, which ended up using their resourcefulness to avoid severe punishments which could include death, without forsaking their ways of life. The Jewish ingenuity came up with staples of Portuguese cuisine today such as alheira de Mirandela, a sausage made with poultry and game meats, shaped to resemble a pork sausage which back then families used to prepare at home and left to cure hanging above the fireplace. Anyone who would come by a particular home and see these meats being smoked, would assume that the christian faith was indeed being practiced, as pork, an ingredient forbidden by Jewish religion, was part of the daily diet.

What does Portuguese food taste like?

After being home to such diverse civilizations, with their own sets of cooking techniques and, even more importantly, preferred ingredients, the historic event which went on to shape the cuisines of the Iberian Peninsula the most was the so-called Age of Explorations and Exploitation when we ‘read’ this part of history with critical thinking. This is when the phenomena we now refer to as globalization truly started.

The Age of Explorations (and exploitation), globalization and Portuguese food today

Sugar cane plantation, around 1905 (photo: Joaquim Augusto de Sousa)

Spices from overseas, sugar and slave trade

The maritime voyages of the Portuguese to Africa, The Americas and Asia molded international trade (and, by means of it, the cuisines) not just for the Europeans but, broadly speaking, for peoples all over the globe. This is when the Portuguese had access to the vast array of spices coming from the Indian Subcontinent, sugar cane which thrived in the Portuguese islands of Madeira, exotic fruits which proliferated in the archipelago of Azores, and incredibly defining ingredients for our cuisine such as potatoes, tomatoes, corn, and even cod.

It must be said that all this rapid expansion was done at the expense of human exploitation. Specifically for the sugar cane plantations in the Portuguese islands of Madeira, slaves were brought from West Africa. In 1485 the number was estimated to be around 2500 individuals, with an annual production of 800 tons of sugar cane – and this is just for the islands of Madeira! By 1500 the figures went up to 3000 slaves/1200 tons, and in 1510 reached 3400 people/1900 tons. To keep things within context, it’s worth noting that Portugal abolished slavery in 1761, but ruled that this abolition would not be extended to its colonies abroad. The decision to end slavery in the colonies did not come until 1869, and was not in fact implemented until the mid 1870s.

The introduction of salted cod in the Portuguese diet

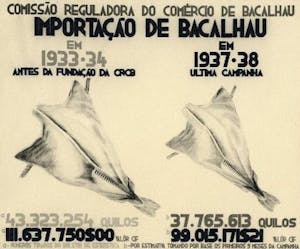

During cod propaganda, between 1934 and 1937, the imports of cod reduced from 43M kg to 37M kg.

Even though Portugal has a strong tradition of salt curing fish, which dates back to the days of the Roman Empire as we explored above, this was normally done with smaller fish caught in the Atlantic waters surrounding our country. When Portuguese sailors reached Newfoundland, in today’s Canada, they came across a bigger species with bountiful white flesh, which they proceed to salt so that they’d have food for their ongoing voyages, but also to bring back home. This is how the immense love of the Portuguese towards salted cod began, and lives on until today. If this preservation technique was developed out of need and carried on before other methods such as refrigeration came about, one would think there’s no reason for salted fish to exist today. Particularly if we’re talking about cod, which does not exist in Portuguese waters and thus has to be imported fresh mostly from the northern Atlantic, to be cured and dried as per our traditions and flavor preferences in Portugal itself. Now-a-days, salting bacalhau has little to do with preservation and it is more about flavor development. Over the centuries the Portuguese grew to love the taste and texture of what is today one of Portugal’s favorite ingredients, which was heavily promoted by the Salazar administration during our country’s dictatorship which ended back in 1974, but that has been an intrinsic element of Portuguese cuisine ever since.

The diversity of Portuguese medieval cuisine

There’s no doubt that, from the 15th century onwards, Portuguese food became way more diverse. Of course the abundance and heterogeneity of ingredients were not a given across all fractions of society, and while the elites would feast on local as well as international delicacies brought in from different parts of the globe, peasants’ diet would still mostly rely on bread, porridges, vegetable and smaller portions of animal protein, which would be compensated with the more readily available legumes, in particular different kinds of beans, prepared in hearty stews with small cuts of meat mostly put in for the sake of adding flavor. For those who could afford it though, the maritime explorations brought in exotic foods from far-flung places, which eventually started being produced locally and hence were integrated as a part of Portuguese cuisine.

Portuguese conventual desserts

Pastel de Feijão cake, during one of our Ethnographich Food Tours

It was also around this time that the repertoire of Portuguese conventual sweets was expanded. If eggs were already a staple of Portuguese cuisine, their use was also common outside of the kitchen. In convents they would employ egg whites to perform tasks such as starch religious habits and glue ornaments on church altars. As it would be a literal sin to waste the perfectly edible egg yolks, their surplus allied with the creativity and the time that nouns had at their disposal, lead to the development of dozens and dozens of recipes which take egg yolks as their many ingredients. Before the Age of Explorations, the sweetening agent of choice would be honey but now, with sugar cane coming from South America and the closer by island of Madeira, sweets were being made with egg yellows, sugar and other notable ingredients like nuts and spices coming from Asia, in particular cinnamon. There are conventual sweets typical in all provinces of Portugal. They normally have egg yolks and sugar as the common ingredients, incorporating other elements which vary per region according to what’s most available and liked: think elements like wheat flour and pork lard in the north, white beans in the center, or dried fruits and nuts in the south.

A small country with diverse terroirs

So when we look at Portugal’s cuisine today, what can we say Portuguese food tastes like?

With over 900 km of coastline, it would be a fair assumption to note that fish is a staple of Portuguese gastronomy. This is true, but Portuguese cuisine is certainly not limited to seafood, particularly not in the more inland or mountainous regions, where different types of meats, especially pork, along with dairy products, make the bulk of the animal protein consumed. Breads, olive oil and vegetables such as different types of cruciferous greens are also defining when it comes to understanding what Portuguese food is all about. In reality, for such a small country, Portuguese food is rather varied from North to South, and when we compare what’s regularly eaten on the coastal areas versus the mountains – it is precisely these regional specificities that we mean to explore with you today.

Regional cuisines of Portugal: food with cultural and geographical context

Our philosophy: observing how Portuguese gastronomy is connected to its background and surroundings

A restaurant in the Beiras Region, where meals are done exclusively with river fish.

At Oh! My Cod Food Tours, our aim is to bring you on a culinary journey across Portugal. During our experiences, which take place both in Lisbon and the Azores islands, we organize tastings for you to not only relish on delicious foods, but also to understand how typical ingredients and dishes came about. With our blog and this article though, we’re taking our time to virtually savor the distinct traditions and dishes from the different regions across Portugal.

Exploring Portugal’s map and getting into the particularities of each region, we will see how local culture is a blend of ancestral knowledge combined with a more contemporary know-how, which when it comes to food, translates into the typical dishes you’ll come across restaurants and homes (if you’re that lucky to dine in with locals!) available in the different regions of Portugal, and which are thoroughly evocative of these areas.

Needless to say, the most representative dishes vary depending on the region, its topography, climate, history, social factors and particular taste preferences, but the use of different ingredients per area of the country isn’t always clear-cut. Of course there are regional particularities on the food you will come across in the distinct areas of Portugal, even more pronounced when it comes to home cooking, but there certainly are cooking approaches and even actual recipes that overlap, and often result in the same dish being cooked slightly different from place to place. After all, the divides that define the regions of Portugal are political borders and man-made frontiers, which have little to do with the way food, culture and daily habits have evolved over the centuries.

We’re exploring the cuisine of Portugal region by region for the sake of making the task more approachable, but in no way we mean to oversimplify the food and drinks heritage of our country. Still, there are some obvious differences when it comes to daily staples. For instance, bread is a given on any Portuguese table but, historically speaking and before we could purchase flour from anywhere in the country or even abroad, the main cereals used would differ according to the qualities of the land where the grains were produced. Wheat would be more abundant in the south, rye would thrive in the arid mountains on the interior north, while white and yellow corn would make cornmeal bread such as broa a popular delicacy in the region of Minho, in the coastal north. Also, if by the coast it would be fairly easy to have access to fresh fish, the interior would have to rely on salted fish (and from the 1853 onwards, when the canning industry started, also tinned seafood) or, most commonly, meats such as pork (fresh and in the shape of of cured sausages and smoked meats, known in Portuguese as enchidos), goat and sheep. Even when it comes to fresh aromatic herbs you see a divide in Portugal: in the north you’d see parsley as garnish in dishes which would normally be completed with chopped coriander in the more Moorish influenced south.

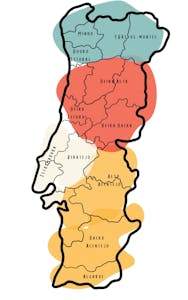

Each color corresponds to a specific food and cultural article in our Ethnographic Food Journal (Design © Silvia Olivença)

If there’s one thing that all parts of Portugal have in common, and which extends to pretty much all southern Europe, is that the concept of hospitality is highly linked to feeding guests and spending time with friends and family around the table, for leisurely meals which involve copious amounts of savory and sweet foods and drinks. We may be biased, but visitors to Portugal would generally agree that, even though our food culture is to a large extent rooted in peasant habits, we are generous when it comes to sharing atop of the dining table the very best we have access to, and precisely because of these humble roots and our food history, we’re masters at turning straightforward but high quality ingredients into delicious meals, most often than not paired with world class yet affordable wines.

Portuguese food habits are a blend of Mediterranean cuisine and the Atlantic diet, relying mostly on fresh foods versus processed ingredients, usually cooked and seasoned with olive oil.

Our intention with the above is to highlight local specificities and point out some products and dishes that you should keep in mind when traveling around Portugal with a keen interest in exploring our country’s cuisine. Each color corresponds to a specific food and cultural article in our ethnographic food journal presented below!

Quick overview of local ingredients and regional approaches to Portuguese food

Minho, Douro and Trás-os-Montes: the cuisines of Northern Portugal (article here)

We shall start our trip up north, in the Minho region, where Portugal’s most popular soup, caldo verde, prepared with a potato puree base and shredded collard greens originated and it’s still much beloved today along with the local cornbread known as broa. We will explore the local ancient specialities that use pigs literally from nose to tail, including their blood (think dishes like sarrabulho) and unique desserts like pudim Abade de Priscos (aka bacon pudding).

Passing by Porto and the Douro region, we will look into how Port, Portugal’s most famous fortified wine came to be, as well as why Porto’s residents are affectionately called tripeiros, that is, tripe eaters. But we won’t just focus on ancient recipes! Instead, we will also explore more contemporary creations like Francesinha.

Going inland but still up north, we’ll reach Trás-os-Montes, a region literally named “behind the mountains” that has had its people, traditions and food habits linked to its hard to cultivate soils, but where some of Portugal’s best cured sausages come from. After all, Vinhais is in Trás-os-Montes and this town is no less than “Portugal’s meat smoking capital”.

Central Portugal and the cuisines of the Beiras region (article here)

In the center of Portugal we find three regions, the Beiras, which are intertwined but that do have their own distinct characteristics. Beira Alta is home to mainland Portugal’s highest mountain, Serra da Estrela, where one of our most famous cheeses, queijo da Serra, comes from. In Beira Baixa, whose landscape is dominated by mountains, goats and sheep thrive, not only for cheese making (and, actually, also wool production), but also as a source of meat. This is where you can taste the unique maranho, that is stuffed goat’s stomach, served on festive occasions. Traveling towards the coast we’ll reach Beira Litoral, where in the charming city of Aveiro (also known as “the Venice of Portugal” because of its many water canals) you’ll find one of Portugal’s most cherished conventual sweets, ovos moles.

In and around Lisbon: Typical foods in Estremadura and Ribatejo regions (article here)

It’s in Estremadura, the province to which Lisbon belongs to, that you will most obviously notice the influence that the Atlantic ocean has on Portugal’s food habits. We’ll get into the local craze for sardine season, but also all other sorts of fresh fish usually grilled over charcoal. Of course we wouldn’t leave our study of the Lisbon region without investigating where the famous Portuguese custard tarts, pastéis de nata, really come from, and why they have even become a symbol of Portuguese cuisine abroad.

Inland from Lisbon there’s the Ribatejo, a region whose name literally translates as the riverbank of the Tejo river, known in English as the Tagus. This area has been shaped by its pronounced agricultural and equine traditions. This is where Portugal’s rice production concentrates, focusing on the local grain variety Carolino, which is essential to prepare a lot of our staple dishes such as seafood rice, duck rice, and particularly all the loose and saucy rice preparations we often consume with grilled and fried fish.

Alentejo and Algarve: culinary traditions of the South of Portugal (article here)

Heading towards the south we’ll pass by the Alentejo, popularly known as “Portugal’s bread basket”, where you’ll come across endless fields of wheat (which is turned into bread and, in turn, into bread porridges and other dishes that have stale bread as a key ingredient), olive trees, grapevines, and where it’s also common to see free range black pigs feeding from the wild, before they are turned into some of our country’s most prized delicacies, such as the porco preto Iberian cured ham (akin to pata negra in Spain).

In the very south, the Algarve region seamlessly combines Mediterranean culture with Arabic influences. Besides the abundant fish and seafood which would be expected in a coastal region, the Algarve is home to intricate sweets made with ingredients such as honey, figs, almonds and other nuts, which are undeniably linked to the times of the Moorish occupation in the Iberian Peninsula.

Azores Food and Wine Guide (article here)

Azores Food and Wine Guide (article here)

About two decades later, Portuguese folks started exploring and colonizing the nine islands which make up the Azores, and which were later also populated by other nationalities. As they’re located in a strategic point between Europe and the Americas, the islands were very coveted by different nationalities (such as English, French and Dutch), which were also devoted to maritime explorations back in the 15th century and afterwards. The Dutch were particularly influential in the Azores, bringing with them their cow farming traditions and cheese making skills, which explain queijo flamengo (literally Flemish cheese) as one of the most common cheeses in Portugal today (this is the regular sliced cheese you get when you order a cheese sandwich in Portuguese cafés, and which also stands out in the supermarket thanks to its bright red wax casing).

The Portuguese Madeira island’s gastronomy

Traveling away from mainland Portugal and into the Atlantic ocean, we find the Portuguese archipelagos of Azores and Madeira. The Portuguese reached Madeira in the early 1400s, when they were on their way to explore Northern Africa. The islands of Madeira and Porto Santo soon became an ideal place to produce crops which didn’t thrive quite as much as in the mainland, such as exotic fruits and particularly sugar cane which revolutionized the world of traditional Portuguese sweets until then sweetened with the more readily available honey.

Article: to be released in January 2023

While exploring regional particularities of Portuguese cuisine, staple ingredients, typical dishes and unique food traditions, we hope to have inspired you to come with us on a mouthwatering culinary trip across our country. Take your time to understand more about Portugal’s food heritage, to feel how it’s connected to the local setting and, above all, to taste it!

Article by:

Zara Quiroga (freelance food writer and food & cultural leader at Oh! My Cod Pico Trips)

Sílvia Olivença (anthropologist and food guide/CEO at Oh! My Cod Ethnographic Food Tours & Trips)

All photos and digital draw images by:

Sílvia Olivença (anthropologist and food guide/CEO at Oh! My Cod Ethnographic Food Tours & Trips)

Want to more about Portuguese culture and cuisine?

Alentejo and Algarve: culinary traditions of the South of Portugal

In and around Lisbon: Typical foods in Estremadura and Ribatejo regions

10 Portuguese Codfish recipes step-by-step

Pico Wine: one of the world’s most unique wine regions (Genesis – Part I)

Pico Wine: the history of a heroic and subversive wine (Tradition & Innovation – Part II)

Insiders’ view on traditional Portuguese soups